I’ve been a professional photographer for about 10 years. I’m sorry, I should clarify, I’ve been a professional digital photographer for about 10 years. Maybe going on 12 years now. I’m losing track. Before I was a photographer, I was a kid with a variety of cameras. I had a Canon GL1 for video, I had a Sony Cybershot F707 for photos—with 5 whole megapixels. Before that I was badly exposing film on one of my father’s classic Canon cameras.

As a 13 or 14 year old kid, my first digital camera was magical. I loved making photos, but my father’s film camera had a lot of stuff I didn’t care about between me and the images I wanted to emulate. With this digital sorcery, It was easier to get what I wanted, and what I wanted at the time had virtually nothing to do with process.

Before digital, I probably shot a total of five or six rolls of film. I couldn’t tell you what film stock it was. I couldn’t name the camera bodies, or the lenses I used. It was all before any of that mattered, or before I thought image creation would be something I cared about. It was just something my father did and I thought was cool. Surely, I heard all the arguments during the war between film and digital in the early 2000’s, but I put my flag down firmly in the digital camp. From my perspective, digital let me do everything I wanted to do, and required me to do nothing I didn’t want to do. I still stand by that. The war is over and digital won in a landslide.

A funny thing happened in the years since then though. The well ran dry. To create an image is one thing, to enjoy creating an image is another. I, and those within my business, have created hundreds of thousands of images for clients over the last decade—I know how to do this, it’s second nature to me. I could practically do it with my eyes closed. (Don’t worry, if you’re a client reading this, I’ll keep my eyes open).

While I still find a lot of enjoyment in the work I do with my clients, the actual mental and physical act of creating a good image is now just marginally more taxing than blowing my nose. Gradually, the film photographer’s arguments about “process” during the film/digital debate began to ring true. I was getting bored. Not to toot my own horn… well, maybe a little horn tooting…I’ve created a gazillion images I would deem almost “perfect” from a classical standpoint. But with each subsequent win, they were mattering less and less. That little pat on the back I could give myself each time was turning more and more into a vaguely approving grunt.

About 6 weeks ago, a good friend was helping his dad offload some clutter, including an old Pentax ME Super camera. I scooped it up for a cool 75 bucks (suckers). I couldn’t even be sure I remembered how to load the film properly, so I promptly jumped on Amazon and bought a pack of the cheapest film I could buy. I went with Fuji Superia 800, costing me $7 for 96 frames. A few Youtube instructionals later and I had a camera, with film in it, cocked and sitting on my desk ready to use.

The ME Super is a classic consumer camera. It followed a model, the ME, that was “auto” exposure only, or aperture priority, as digital photographers call it. Basically that means the ME model would automatically choose the shutter speed based on the aperture, which is set manually and the ISO, which depends on the film you put in there. The ME Super added a manual mode to the camera, though in a rather janky way. Nonetheless, what I am newly compelled by is the dramatically slowed process of shooting. Not being able to see your images right away is a fun change of pace, but the slow down I’m referring to is the one experienced from behind the camera, the one that is almost impossible to emulate on purpose with a digital camera. The mental process, forced to a crawl. So, I switched it into manual mode and began carrying it with me here and there.

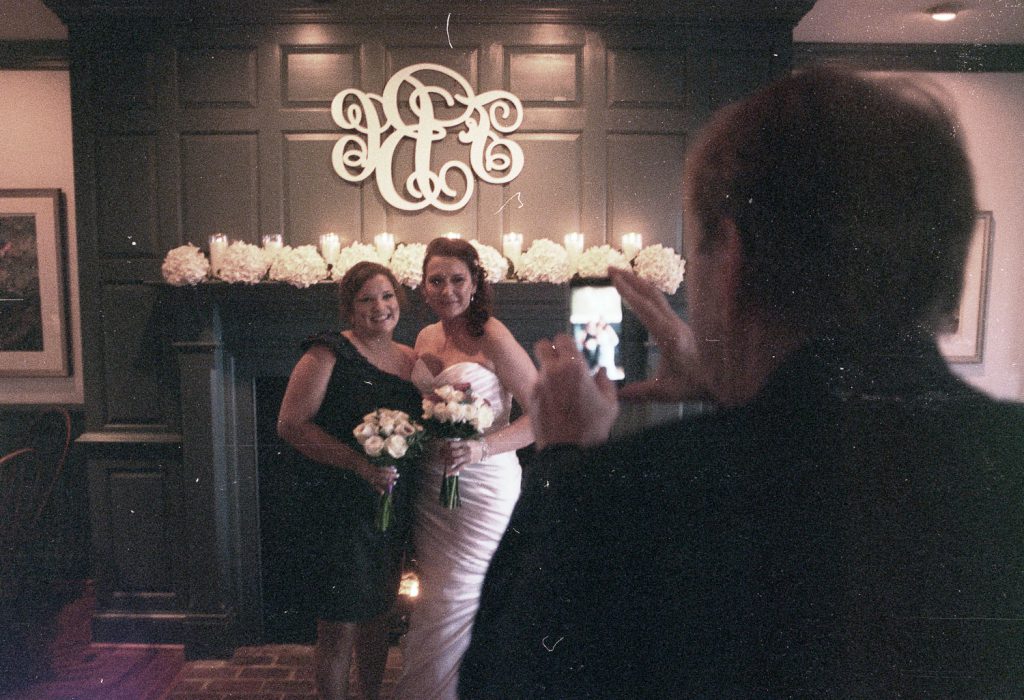

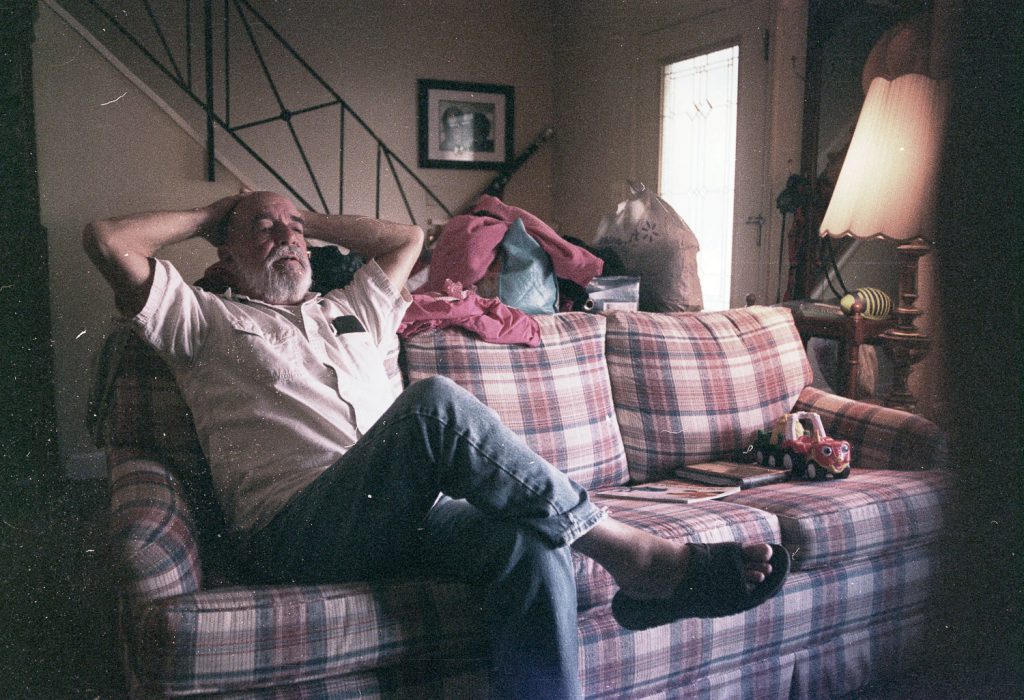

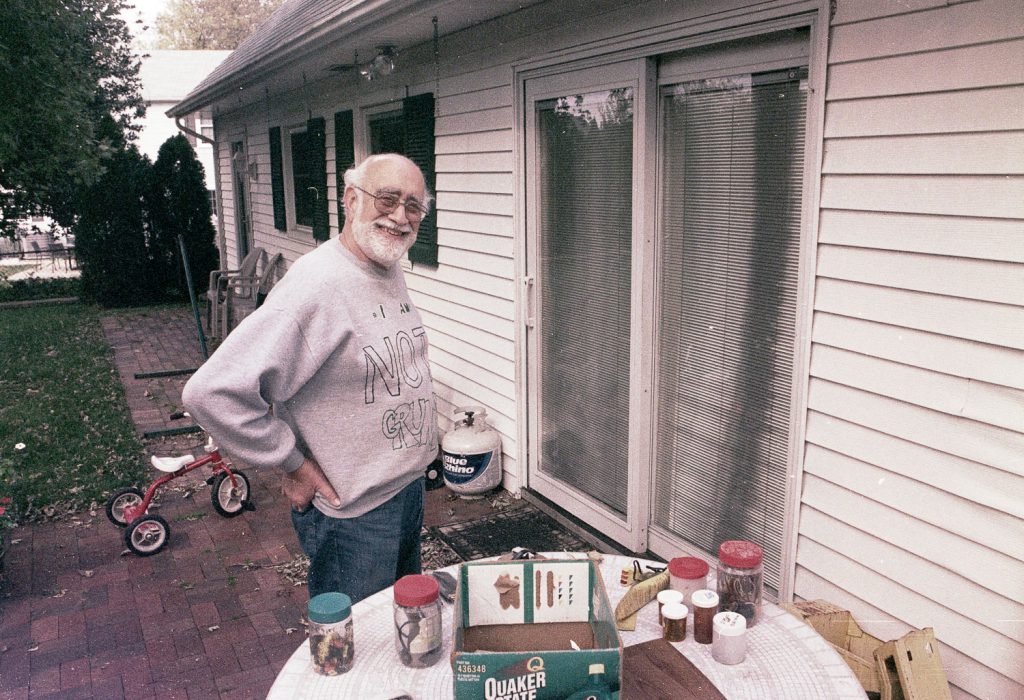

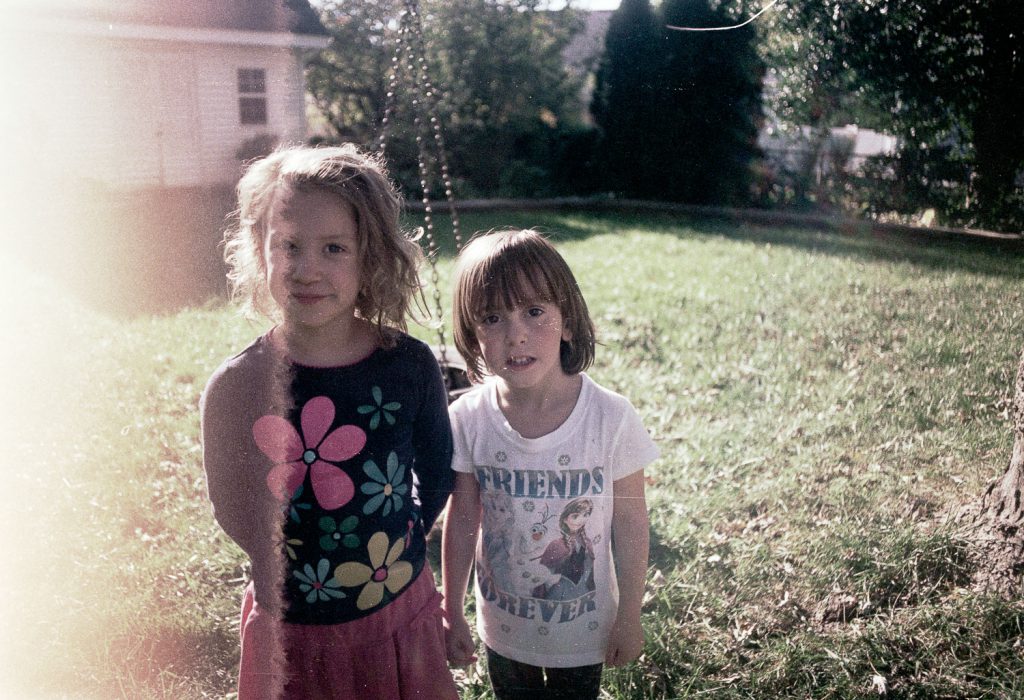

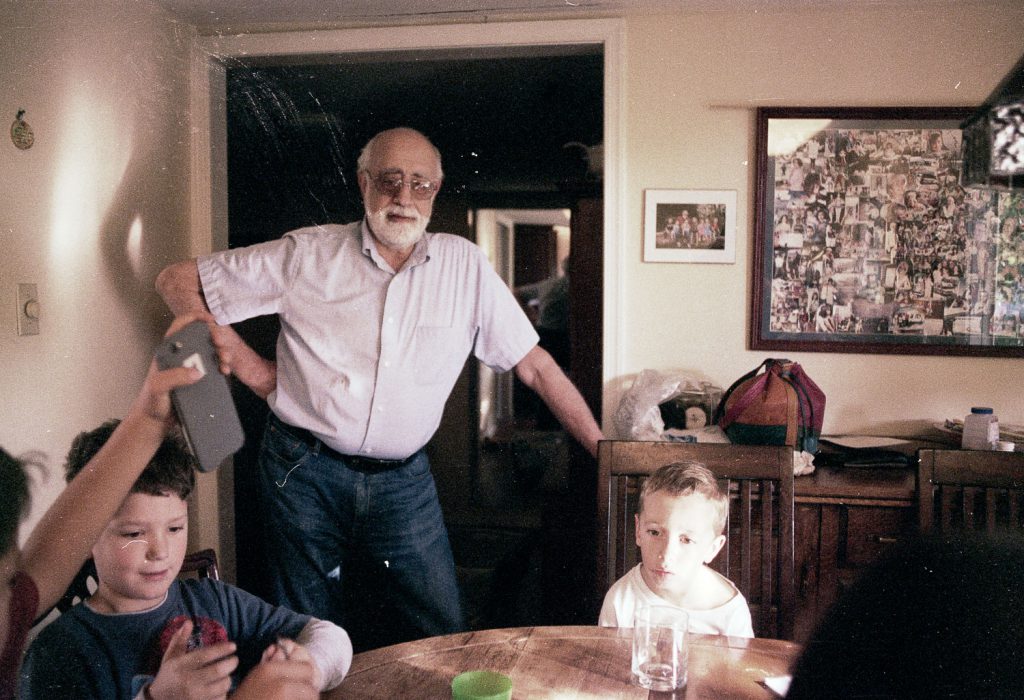

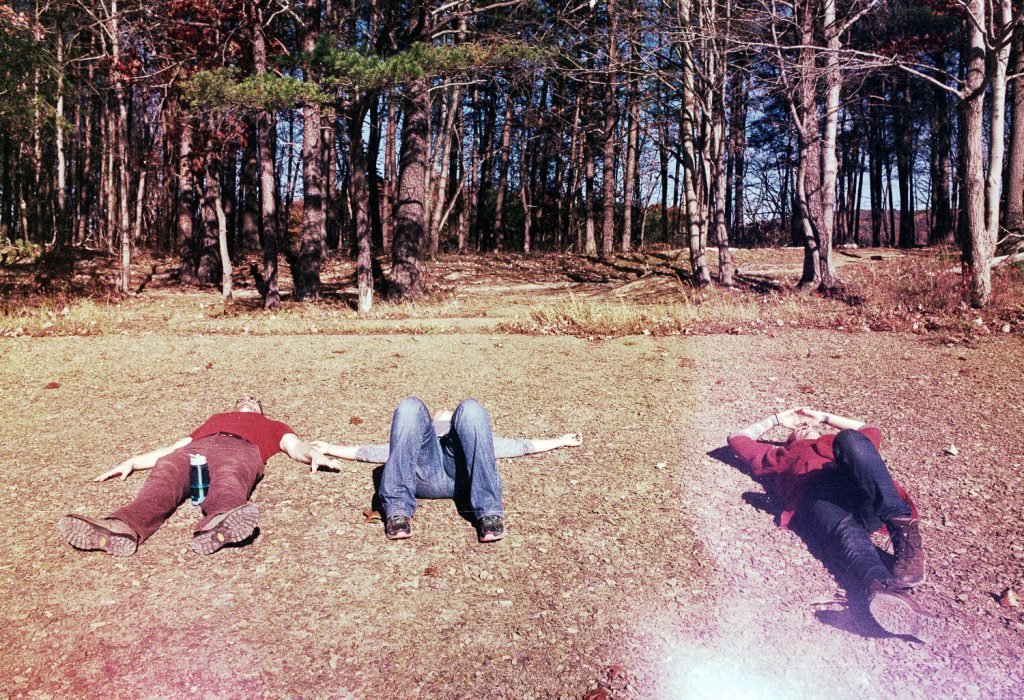

During my first couple rolls of film in 15 years, my goal was not so much to take good images—though there are some keepers below—rather it was to try and translate my intuition as a digital photographer to film. Good thing too, cause I’d have been disappointed if I was expecting photographic magic here.

What I found right away was that I had no good reference point for the dynamic range of the images I was creating. Virtually all digital cameras produce images with dynamic range closer to what our eye sees than what a film camera would capture. So, immediately I was in experimentation mode because I couldn’t clearly visualize the contrast in my scene. Should I overexpose a stop, or underexpose a stop? I would know the answer with a digital camera, but I was in the dark (so to speak) with film. That wasn’t frustrating though, it’s exactly what I wanted.

By the time I got to my second roll, I was getting more comfortable. I still didn’t know what to expect of the images I was capturing, but I was fine with the mystery. Soon I moved onto the second delight which is almost entirely absent from digital photography: manual focus. Digital cameras can support manual focus, but offer pretty much no way to confirm that you’ve nailed it, save for checking the image on the screen. Most photographers skip manual focus altogether, which makes sense if your goal is to create a great image; machines are unequivocally better at focusing a lens than human hands and eyes are. Old film cameras have a handy featured known as a split prism, which gives the film photographer a way to see clearly whether their image is in focus. It just takes way longer.

There was also the question of just how sharp this old lens would be at wide apertures, compared to the pristine modern lenses I’m used to (hint, not very sharp). As a digital photographer, I often focus, then recompose my image. This is a workflow artifact of the autofocus system I use. With this old camera though, would the same workflow suffice, or would the lens be too soft around the edges for that?

Asking these questions as I looked through the viewfinder was a breath of fresh air for this creative outlet I’ve grown too familiar with to really love for what it is.

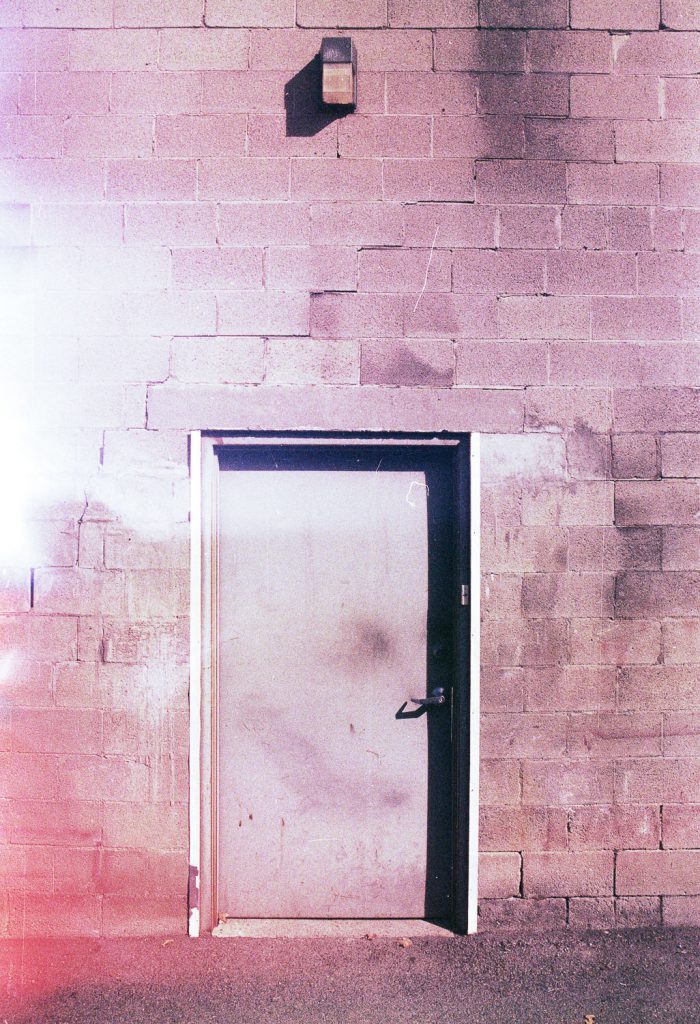

Waiting to see the images was a novelty I can appreciate. As I got the film back, I found more or less what I expected. A lot of underexposed and overexposed images as I tried getting acquainted with the dynamic range. And a lot of images out of focus, as I tried guessing at how usable the wide open apertures are. My expectations as far as film-specific artifacts are concerned, however, were totally exceeded. This camera leaks light with a lot of character, which I love. I can make exactly the image I want with my digital camera any day, but my film camera will add its own random flare, making it more like a partner than a tool.

I’ve absolutely loved what film has given to me as an adult and intend to shoot a roll or two every month. This, however, will probably be the last time you see the bad ones alongside the good ones, so laugh at me for those black frames while you still can, I love those ones too!

How cool! I found an old 35mm camera at a trinket shop. I plan to shoot my first roll of film hopefully over the summer.

Awesome! I’d love to see what you get! Tweet at me! 🙂