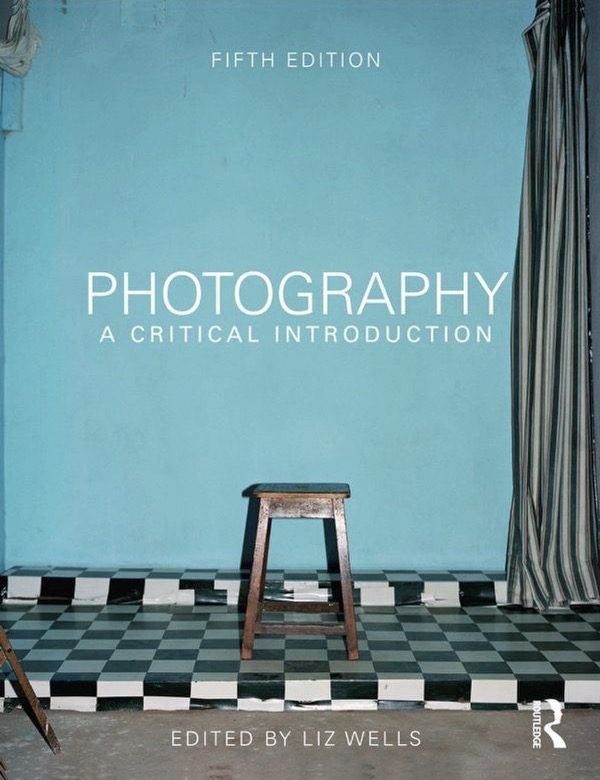

Photography: A Critical Introduction is an academic game of-catch up in the history of photographic development, and especially the debates around those developments. It was a good, exhausting read.

Photography: A Critical Introduction is an academic game of-catch up in the history of photographic development, and especially the debates around those developments. It was a good, exhausting read.

The book, which is in its fifth edition, is on the reading list for the School of Visual Arts MFA. That means its heady and theoretical and almost useless to the majority of working photographers–possibly me included. But that doesn’t mean it’s not incredibly interesting and full of perspectives and cultural summaries that certainly couldn’t hurt. Plus, learning crap like this is how I get my jollies.

The book is broken up into six extensive chapters, written by Liz Wells, Derrick Price, Patricia Holland, Michelle Henning, Anandi Ramamurthy. The book is not truth, but it is truthful. Perspectives and ideas are explored that have been thought about time and time again. Photography consolidates many of the legitimate ways people have come to look at photography and its history, but it doesn’t look at all of them. And without a doubt, the author’s politics shine through.

Presenting historical contexts and references, the authors attempt to trace a path between genres and the influence of political concerns on the medium. The question of whether photography is art is traced throughout the developments, and in the end the answer is still yes and no. Photography has found itself inside and outside the walls of the gallery, and it has seen success in many spheres of influence–art being just one of them.

Chapters cover the telling debates in the history and theory of photography, notably how the concept of ‘photo equals truth’ quickly seeded itself and has been slow to shake, in spite of advances in digital technology that deeply undermine that assertion. The book explores the genres of documentary and photojournalism, which were, among other things, a logical outgrowth of people’s trust for the photographic image. It also covers concepts surrounding personal portraiture and its relationship to the painted portrait, photography’s relationship to the human body, and the commoditization of photography and what that means to its seat in the world of art.

The benefit and profound limitation of this book is that without research into other historical perspectives, and without a critical eye, a reader is apt to take the espousals of this book as truth.

Liz Wells says, in the final chapter:

“…information does not substitute for critical thinking. A description of what a photographer has achieved is not the same as an interrogation of the significance of his or her achievement…”

This book was dense, with each chapter costing me almost three hours. The mere achievement of finishing and understanding what was written is apt to lead the reader to simply accept what was said about history. But that’s not enough, there are other perspectives. Our own diligent search might produce very different perspectives–the looking is a kind of art in itself. What this book offers is a way not to reinvent the wheel–or, at least, not to do it on accident.

Recent Discussion