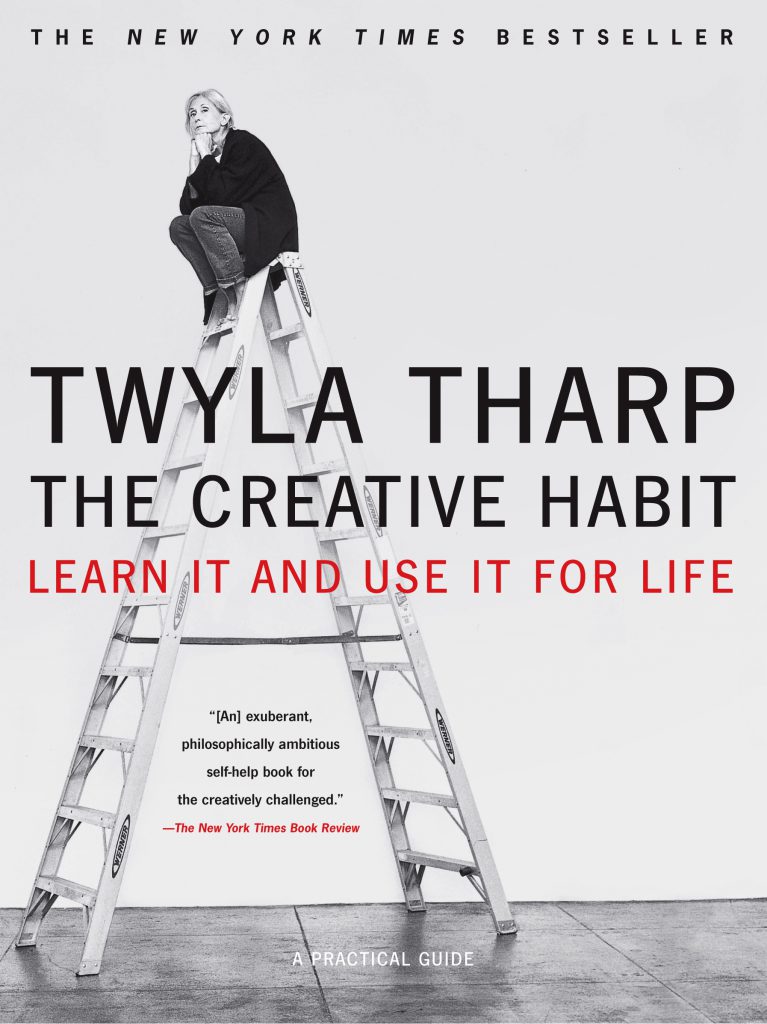

Creativity Habit is a book by an accomplished choreographer named Twlya Tharp. She wrote a book for creative people, but she had to dress it up like it was for everyone. At least I think that’s what happened. Her’s is a practical guide for day to day creativity. Although, honestly, it’s not that practical unless you live and die by the art you create. Luckily, I kind of do and I thought the book was great.

Creativity Habit is a book by an accomplished choreographer named Twlya Tharp. She wrote a book for creative people, but she had to dress it up like it was for everyone. At least I think that’s what happened. Her’s is a practical guide for day to day creativity. Although, honestly, it’s not that practical unless you live and die by the art you create. Luckily, I kind of do and I thought the book was great.

In the book

The book opens with an attempt to to sooth the fear of the blank page. Or the empty room, in choreography speak. It’s the fear of getting started, and it’s definitely real. One of the treacherous things about being a creator is the empty space before you put something down. Having too many options tends to make none of them seem all that appealing. And that’s what creators face when they start, an infinite set of options.

To help get past those getting-started jitters and the never-ending excuses not to get started, she recommends preparation rituals. Now, I know some artists who think of the concept of ‘rituals’ as antithetical to the concept of art. But I, and Tharp, beg to differ. Rituals, as Tharp explains, are our best defense “when you are most at peril of turning back, chickening out, giving up or going the wrong way”. I know this frame of mind well. When a project is on the table, especially a collaboration of some kind, there’s a tension in the air. Everyone knows the stakes are about to go way up and excuses have a way of sounding more and more legitimate. The sorts of things Tharp suggests for preparation are things like planned solitude, going for a particular walk or giving up something specific for a week. But she would tell you herself that it doesn’t much matter what it is.

Tharp urges readers to create in the way that feels most natural to them. The way that feels most at home. She calls it creative DNA. She tells a story about asking a young painter to write her an essay about why he wants to paint. When he returned 500 words and barely mentioned color once, she wondered whether his creative DNA had him pegged for a writer instead. And she really thinks it’s in an artist’s best interest that they stick to what’s ‘in their blood’.

“I wonder how many people get sidetracked from their true calling by the fact that they have talent to excel at more than one artistic medium. This is a curse rather than a blessing. If you have only one option, you can’t make a wrong choice. If you have two options, you have a fifty percent chance of being wrong.”

I respectfully disagree. Those are the makings of self-fulfilling prophecy. But, I digress.

Tharp continues with a discussion about memory. Specifically, and most interesting to me, muscle memory. Skilled artists are able to create in their medium from their gut thanks to muscle memory. Or, something like it. She’s talking about almost automatic motions we can go through when we’re really good at something. We can think while we’re walking because we don’t have to think about walking. If I wanted to create a photo from the heart, I couldn’t let the technical interaction between me and my camera get in the way. An almost automatic, or muscle memory-like interaction with my tools would be necessary.

Effectively developing all of the skills to work within a medium without thinking about it, and to judge your actions well, requires organization. So Tharp says, “you have to get a box before you can get outside the box”. She’s talking about cataloging, in a sense, the things we do and engage in. In a practical sense, it means grouping everything about one project in one place. You get to start seeing things that can be shared between them. And, less obviously, the organization becomes a kind of catalogue of skills. For example, in this project I develop skills in lighting technique, and in this project I develop a better sense of shape and balance.

To fill all those boxes, and to ‘get out of them’, Tharp talks idea generation. She calls this scratching. It’s like wading through waters of content others have created or are happening on their own, wondering about them, and then going in another direction. Why was this love song in this tempo? What if this love song had been written from the start for another tempo? It also means becoming keenly aware of inspiration in the environment and circumstances around us. Not simply becoming aware of them, but questioning them, becoming ornery with them and demanding alternatives from your mind.

If we’re diligent in our scratching and we’re not running in fear from our opportunities to create, then learning to accept accidents becomes crucial. Luck, in Tharp’s view, is when two competing parties agree. Any two parties. People compete with each other. People compete with circumstances. People compete with things. But when they agree its lucky. Take for example your phone battery and the video of your friend drunkenly jumping over a fire-pit. It was lucky you got the video before your phone died. Time and the phone’s batteries were against you, but at just the right moment, they agreed with your desire. Accidents are like the opposite of luck. Although you plan, sometimes circumstances collude and create ‘accidents’. But, as she says, on the flip side, you can’t get lucky unless you plan.

One way to improve judgement, Tharp says, is to give your work a ‘spine’. Something that runs the length of your project and attaches to nearly every element. The spine could be a thought provoking question overheard on a train “is anything real”. That could become the spine of an entire piece. The spine could also be born from other works of art, but Tharp is clear that it’s not copying. It’s about giving something structure and consistent meaning.

Copying is easy. It’s creating something original, even from an existing source, that is difficult. Tharp makes a distinction between craft and skill. The craft is what you do, the skill is how you do it. Being a skilled craftsman would mean knowing your craft inside and out. What she says here is particularly relevant to the working artist, especially since so many of them today have been educated with specialized training. To be a master of something, singular mastery isn’t enough. Proficiency in surrounding disciplines is crucial too. For example, a working photographer doesn’t get the luxury of just being a photographer. They also have to be a tech-wiz and a pretty decent marketer.

The life of a working artist is diverse and complicated, so far as cultural norms are concerned. Tharp tackles the topics of ruts, grooves and failure that often accompany that abnormality. Her discussion of failure is perhaps the most interesting. There are two broad categories of failure that she notes, private failure and public failure. Private failure is taking 1000 pictures and throwing away 998 of them. Public failure is throwing away the wrong 998. She wants to make a distinction between public and private failure because private failure produces growth, it’s good for us. Public failure has the actual potential to ruin us, or at least our spirit.

The final chapter in Tharp’s book was, I think, the real “Habit” part of the title. It talks about the day-ins and day-outs of creativity and the challenge of facing the blank page, or the empty room, over and over and over. She urges readers to develop a ‘creative bubble’. For some people, it’s a quiet studio, for others, the bubble goes with them everywhere and anyone inside of it is fair game. The bubble is the space where things go from facts to inspirations to creations. The bubble is all of these things she’s discussed, wrapped up into a lifestyle that perpetuates them with anything that enters the bubble.

In Conclusion

As a person who needs to think creatively on a daily basis–like, for money–I found the book inspiring. It’s intended to be practical, but there are too many words. Instead, there is a lot of philosophy bringing it all together. For most people, philosophy isn’t very practical. But for the artist it definitely is.

Recent Discussion