I went to the Gay Pride parade in DC a few months ago. It would be my first time going, because I didn’t much feel like I had any business being there. Of course, I was wrong. There was a world of curiosities waiting there for me.

I went to the Gay Pride parade in DC a few months ago. It would be my first time going, because I didn’t much feel like I had any business being there. Of course, I was wrong. There was a world of curiosities waiting there for me.

I stood on the sidewalk watching. Friends who were with me thought I was having a miserable time. I’m sure that’s the face I was unintentionally wearing. It’s also my curiously-cautiously watching and looking for meaningful analysis face.

That’s what I was doing. Watching and trying to find meaning and connections. Without just the right amount of alcohol, I’m someone who will watch from the sidelines. I’ll try to figure out where I fit in before I throw myself into something.

It’s admittedly a little neurotic. You won’t usually see me dance. You won’t see me volunteer to be the captain of the kickball team, in fact, you probably won’t see me on the field at all. If you take me bowling, I’m going to do my very best not to care how very, very badly I’m throwing the ball down the lane. You’re supposed to throw it, right?

My father says that he was a late-bloomer in almost everything he ever did. Well, me too.

I spend hours, days, weeks, and (in the case of my own sexuality), decades, sitting on the sidelines analyzing and testing mental models for myself. People occasionally tease me for staring off into space when I have no “supplementary” reason to do so. But that’s alright. Attempting to understand my world, and the distortions created while looking through my own lens, is something that I deeply enjoy. Practically speaking, my approach to life has its drawbacks. I probably do a lot more thinking, in an active sense, than actually doing.

So, some time after the Pride parade, I found myself again with the group of friends from that day. We were eating dinner at The Queen Vic. Conversations wandered to the experience of the day. It having been my first time to the parade, the veterans were interested in my take.

It was, unfortunately, incomplete.

My perceptions of the parade were distorted, at least in part. The commercialism and extremely loud, overt sexuality both seemed to work in tandem to create in me a sense of marginalization. A feeling something like what women must feel while watching beer commercials.

My take on the experience produced a response in my friends that was perhaps less than tactful. At another time in my life, it might’ve turned into an argument, probably even a fall-out considering the topic. But I hold less firmly to my ideas these days, and prefer to remain malleable.

I listened to the criticism: “You don’t know where this stuff came from, you don’t know the history.”

I really didn’t like that criticism, but couldn’t rightly deny it. It’s true, I’ve spent countless hours learning all about the currents of my mind. I’ve analyzed my own history to death, and I’m still probably off the mark. But I had never taken time to consider the group history of gay and lesbian people in general. I watched the Pride parade through a lens that had, thus far, only looked at what was inside, and conclusions were drawn predictably.

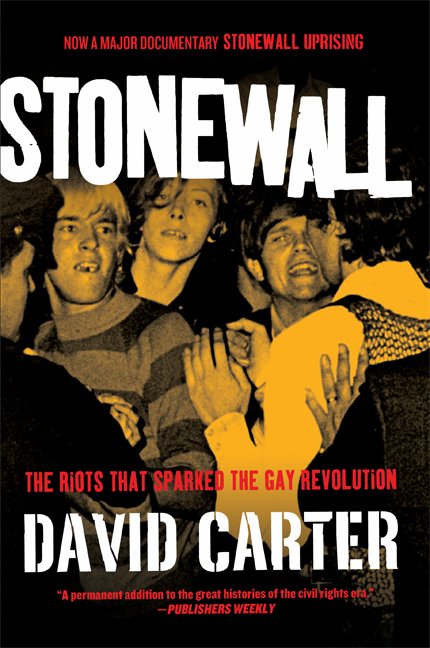

It was this that brought me to David Carter’s Stonewall. A meaty, surprisingly readable and well balanced collection of accounts of the Riots that happened outside the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar, on June 28th, 1969. The riots, which lasted many days, were sparked when the Mafia-run gay bar was raided early in the morning. Hundreds of people, fed up with laws that criminalized them, and corruption that confined their social activities to establishments run by the mob, rioted through the night, and returned night after night throughout the week.

The Stonewall Riots are widely seen as the crucial first step in the modern gay rights movement.

An interesting aspect of the Stonewall riots, I thought, was their relatively peaceful nature. Sure, people were throwing bottles, and rocks, and punches, lighting things on fire, taunting riot police and ridiculing and embarrassing the regular police. But Carter notes that there was only one known fatality: A cab driver who was startled by the crowd and had a heart attack. Aside from that, there was apparently more comedy and showmanship among the rioters. Almost as if the goal was mockery, not violence.

Carter puts a lot of context around the rioter’s actions. Homosexuality was a de facto crime. Their social gathering was deemed “unruly” or “disruptive behavior” by the state liquor authority. So bars who made a clientele out of the gay community would not be able to obtain a liquor license. Bars who had a lot of gay customers, or who sold liquor without a license would be raided, and the homosexuals within would often be arrested. As a result, the only place homosexuals were able to socialize was in mafia owned bars who paid off the cops.

Meanwhile, as Carter explains, homosexuality was criminalized and clinicalized. Officials and the general population equated it to pedophelia and communism. At best it was seen as mental illness, and deserving of pity. But disdain was the most common. Laws requiring people to wear at least three articles of gender-appropriate clothing forced gays and lesbians to restrict their behavior to society’s gender-normative guidelines. The absence of laws protecting their jobs led to many homosexuals being fired and unable to find work if they were ever discovered.

There were homosexuals in every level of society–but they were invisible everywhere except for the poorest and the most desperate. Images of homosexuals in media was usually vile, if not entirely absent. Carter says “When Hollywood made a film with a major homosexual character, the character was either killed or killed himself.”

So it was a pretty shitty time to be gay. You were either society’s outcast, or you were living under the enormous pressure of secrecy and emotional isolation.

The last third of Stonewall looks at the rapid effects the riots had on the gay rights movement. Within a year, dozens if not hundreds of gay-oriented publications began to spring up, and subscribers climbed rapidly from a few hundred to hundreds of thousands. Carter quotes an unknown man after the riots saying “Gay power is here! Gay power is no laugh. There are one million homosexuals in New York City. If we wanted to, we could boycott Bloomingdale’s, and that store would be closed in two weeks.”

The way Carter tells it, New York City at the time was a champaign bottle someone shook up, and the raid on the Stonewall Inn popped the cork. Within the first year, gay men and women marched, and startled the onlookers who weren’t sure they were really seeing what they were seeing. Carter’s retelling makes it sound like one of those stereotype breaking moments for a lot of people. And it probably was. And there were apparently some defining moments for the movement in there too.

Carter describes “As the sun shone brightly, more and more men removed their shirts, lending an erotic cast to the march”. Sounds familiar. But interestingly, the other elements seem to imply something else as well. Carter continues “Signs included: ‘I am a lesbian and I am beautiful,’ ‘Hi, Mom!,’ ‘Smash Sexism,’ ‘Me too’ (on a dachshund), and ‘Homosexual is not a four-letter word.’ “.

I think I realized here the disconnect during my experience at the Pride parade. The word “pride” itself.

The attitude in 1969 and the early 70’s in New York, it seems, was, “I’ve been uncomfortable my whole life, and I’ve survived. Now I’m going to be whoever I want to be, and you’ll just have to be uncomfortable for a while”. Pride in something they had no control over–as silly as that might be on paper–was the necessary antidote to their marginalization. Not just to the outside world, but to themselves.

Somewhere in the mix, “pride” seems to have lost it’s meaning. And of course, I’m a novice in this opinion, but in some parts of the country, maybe even its value as a stabilizing agent. I’ve never been to a Straight Pride parade. And while I understand that the images in virtually any public show is going to be geared at heterosexual people, it isn’t itself celebrating that sexual orientation. It’s celebrating the new year, or a sports win of some kind. It’s celebrating something that a people group did, not something fundamental about themselves–like their blood type or something.

I can’t help but feel like there is a natural next phase, and whether it’s going to look much like it does today.

In Conclusion

David Carter’s book felt complete, and reasonably well balanced from a political standpoint. His own conclusion of the order of events during the riots sided with the account which came from the Police Chief. Although it doesn’t read in an exactly chronological order, it’s close enough to feel like a narrative. The book is meaty–each chapter costing me about 45 minutes. And the references are a third the length of the book itself. So it’s heavy for casual history reading.

Like myself until I finished this book, most people gay or straight seem to know very little about the Stonewall riots, or their significance to the present day movement and culture at large. So I recommend it. Taking all of my bias into account, I definitely recommend it.

I’m looking foreword to attending the Pride parade again next year with a fresh set of eyes provided by Stonewall and a whole new ground for my habitual, neurotic analysis.

Thanks for your transparency. It’s inspiring!